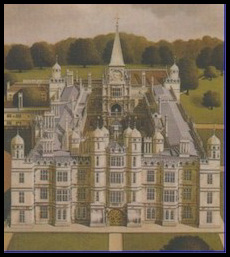

The Great House

The ancient manors and houses of our gentlemen are yet and for the most part of strong timber, in framing whereof our carpenters have been

and are worthily preferred before those of like science among all other nations.

Howbeit such as be lately builded are commonly either of brick or hard stone,

or both, their rooms large and comely, and houses of office further distant

from their lodgings.

The ancient manors and houses of our gentlemen are yet and for the most part of strong timber, in framing whereof our carpenters have been

and are worthily preferred before those of like science among all other nations.

Howbeit such as be lately builded are commonly either of brick or hard stone,

or both, their rooms large and comely, and houses of office further distant

from their lodgings.

Those of the nobility are likewise wrought with brick and

hard stone, as provision may best be made, but so magnificent and stately as

the basest house of a baron doth often match in our days with some honours of

a prince in old time. So that, if ever curious building did flourish in England,

it is in these our years wherein our workmen excel and are in manner comparable

in skill with old Vitruvius, Leo Baptista, and Serlio.

— William Harrison, The Description of Elizabethan England, 1577

The familiar half-timbered Tudor house is becoming quaint and old-fashioned. If your family is still occupying a house of this style, it's time to re-design, remodel, or relocate.

Building and remodeling are all the rage—not just palaces and monuments but country houses and even yeoman farmhouses.

If you have an ancient family property, you may be adding a new wing with larger chambers and more windows.

If your family is up-and-coming, you may be busy in the land market, acquiring property on which to establish a notable seat suitable to your current dignity. Or you may be modernizing a monastic property acquired by your father or grandfather in the time of Henry VIII.

Those looking for preferment must be prepared to entertain the Queen when she is on progress—sometimes on a moment's notice. The importance of a commodious Great Chamber, a fashionable dining parlour, and galleries for entertaining and display cannot be underestimated.

At the same time, knowledge of classical treatises on architecture and continental trends based on them is a sign of your education and taste, and a new or expanded house in the latest fashion is a symbol of your rank and power.

The stone for all this building may come from your own quarries, if you have them. Abandoned monasteries often provide dressed stone, timber, and paving tiles, as well as tin and lead for the roof.

Bricks and tiles are usually baked on site from local clay.

On window glass

Traditionally, many building elements are thought of as moveable: shutters, doors, window frames, chimney pieces, wainscoting, even staircases. As the great house becomes more of a symbol of family permanence and power, these elements come to be seen as fixtures rather than furnishings.As late as 1567, glass is thought too fragile for constant use. When you're not in residence, you may instruct the staff to remove the glass panes and place them in storage. They will fill in the space with panels of translucent horn or woven lattices fixed into wooden frames.

As glass becomes cheaper, and windows more numerous, they come to be seen as a permanent part of the installation.

With the proliferation of glass, the new houses springing up in the countryside have a tendency to glitter. (Happily, no one will think to tax them for another 100 years or so.) The countess of Shrewsbury's great house in Derbyshire indulges the passion for glass to such a degree that people say: Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall.

On design

Architecture is a newly revived science, largely promoted in England by Dr. John Dee (1570) and John Shute (1563). It is not a profession but a gentleman's avocation.If you cannot import an architect from Italy, you probably design your new house yourself, with assistance from a Master Mason or Carpenter, with a Surveyor of the Works to supervise the workmen.

Some things never change: In 1594, Lady Shrewsbury sought legal redress against a workman who had absented himself from work already begun and paid for.

The principal influences:

- Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture (1st century Roman)

- Leo Baptista Alberti, On the Art of Building, 1435

- Serlio, On Architecture, 1537

- John Shute, The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture, 1563

- Palladio, The Four Books of Architecture, 1570

Classical ornament includes columns based on modern interpretations of Roman and Greek models, molded terra cotta medallions, and symmetrical facades.

Don't feel obliged to copy anything too closely, however. Even your neighbors are borrowing only the ornamental elements that please them, rather than whole floor plans.

In fact, your new facade may be totally unrelated to the style of the room plan behind it, which is likely still traditional. If you are merely remodeling, you may choose to tack on a new facade to your present but unfashionably medieval building.

Propriety arises when buildings having magnificent interiors are provided with elegant entrance courts to correspond; for there will be no propriety in the spectacle of an elegant interior approached by a low, mean entrance.

— Vitruvius

Sources

Nicholas Cooper, Houses of the Gentry, 1480-1680,

Malcolm Airs, The Tudor and Jacobean Country House: A Building History,

Lena Cowen Orlin, Elizabethan Households,

![]() Domestic Details

Domestic Details

![]() In My Lady's Chamber

In My Lady's Chamber

![]() Plan of Ingatestone Hall, a Country House of the

Latter Sixteenth Century

Plan of Ingatestone Hall, a Country House of the

Latter Sixteenth Century

![]() Gardens in Season

Gardens in Season

28 March 2008 mps