Music by the book

Music is threaded through the Elizabethan day. Everyone sings whether at work or for pleasure, and many people play instruments.

Every gentleman, most ladies, and practically every other adult in England is, if not an accomplished musician, at least acquainted with singing in harmony.

The queen herself was an accomplished player of the virginals (an English harpsichord); her father had been a very gifted musician. In fact, Henry owned rooms full of instruments, and could play them all.

William Byrd acknowledges that not everyone is blessed with a good voice, a gift "so rare that not one among a thousand have it." Still he felt that one should learn to sing in order to avoid wasting a rare talent.

The English school of madrigals flowers from about 1588 and on beyond the reign. The earliest madrigals are based on Italian models and often are simply the same song with English lyrics.

In general, music is a part of some other event—dinners, dances, parties, plays, masques—and not performed as a concert. Professional musicians are most likely to be instrumentalists.

Any noble household may employ servants specifically for their singing voices, even if that is not their primary duty. Great nobles may keep consorts, choristers, and players for their own and their guests' entertainment.

A set of like instruments playing together are a consort, because they consort with each other. A play on these two meanings appears in Romeo & Juliet (III, 1). Tybalt says, Thou consort'st with Romeo, to which Mercutio replies, What! Dost thou take us for minstrels?

A set of unlike instruments playing together is a mixed or broken consort.

Instruments of the same family (such as all recorders, all viols, etc.) are a noyse of instruments. When a complete family is used (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass), it is referred to as the whole noyse.

Music books with familiar notation are in print. Thomas Morley and John Dowland have the most music left to us today, possibly because they published so much of it themselves.

Italian madrigal books are also available with songs by Palestrina and others.

Tallis and Byrd jointly held a monopoly on the printing of music books and manuscript paper. Tallis died in 1585; Byrd later passed the monopoly on to his pupil Morley.

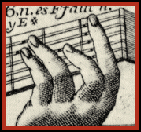

Nearly every printer was publishing madrigals as well as part books for vocalists. These are printed with each part facing in a different direction, so four people can stand around one copy of the music.

Tallis, Byrd, and Dowland all created sacred music, especially when hired for that purpose by a cathedral or, best of all, by the Chapel Royal. Any position with the Chapel Royal is extremely prestigious, although music is no occupation for a gentleman.

Books for the lute include The Schoole of Musicke by Thomas Robinson. It featured music for the lute, pandora, orpharien, and viol de gamba. Another instructional book was Ravenscroft's A Briefe Discourse of the true (but neglected) uses of charactering the degrees.

Morley's A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (1597), an important treatise on music theory, is still in use today.

For Your Eyes Only: Because of their ability to travel and mingle in all sorts of circles, musicians are often employed in espionage on the Continent. Thomas Morely occasionally served in this capacity for Robert Cecil and possibly Francis Walsingham.

Sources:

Lang, Music in Western Civilization

Correspondence with early music professional Tim Rayborn, Cançoniér, Berkeley, CA www.timrayborn.com

Correspondence with Ingrid Waterson, University of California, Irvine

12 March 2010 mps